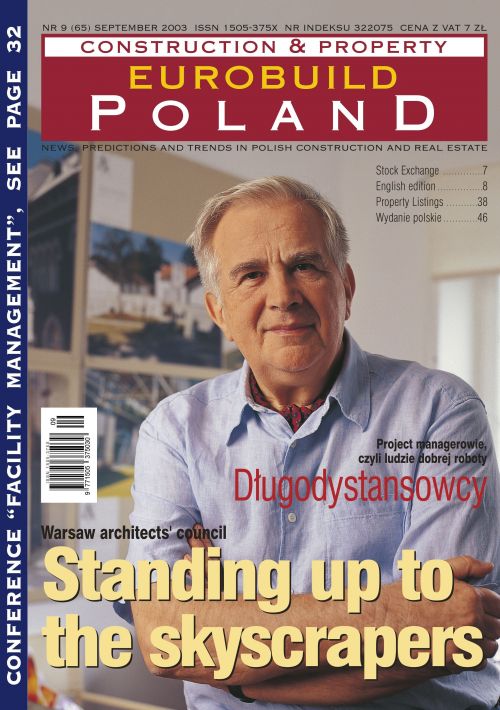

Standing up to the skyscrapers

Along with the election of Lech Kaczyński as city mayor last year, came a commitment to restore both the position of Chief Architect for Warsaw and the advisory council of the top architects in the capital, to advise the mayor on spatial planning. This after a hiatus, during which council members will assert, a number of serious planning errors were made in the city

The 'Rada Urbanistyczno-Architektoniczna Warszawy', as it's called in Polish, has been meeting every Wednesday at 5pm for about five hours a session, for the past three months or so. It consists of fifteen members including the chairman Andrzej Kiciński, of whom most are professional architects. Though it is a purely advisory body, with no actual administrative power, it very much shares many of the concerns the new mayor has for the city's skyline and will consult with him in tandem with the Chief Architect Michał Borowski.

An end to chaos

Whether or not it is a complete coincidence, it was during the mid to late nineties after the previous architects' council had been disbanded, (in 1993), that Warsaw's CBD shot skywards with some abandon. The result is a sprawl of neck-straining structures beyond the Palace of Culture, which have left both the city's pre-war architectural heritage and arguably much of its population behind.

"There was no such body in the mid-nineties and because no professional opinions were given, the spatial results of some decisions were not studied and there were some bad consequences," says Paweł Detko of DJIO Architekci, and a member of the council.

Another participant, Piotr Szaroszyk of Szaroszyk & Rycerski Architekci, cites other European capitals, such as Helsinki and Berlin, as models to emulate when it comes to urban planning, and whilst he accepts that Warsaw is far from being able to follow suit, it could still take a leaf from either of their books.

"Helsinki's spatial and town planning is very different to Warsaw," he says, "because they don't have private land property inside the city - everything is communal. Architects there plan everything: streets, the shapes and sizes of buildings etc. If a developer or an investor comes to build something - they can design apartments or fauades but the rest is already done. Helsinki is an example of where there's total control." And of Berlin: "In Germany they have five times more architects than in Poland, so they protect their market much more than here. They don't let people put their junk in their city and Warsaw does."

It should be noted however, that this is not a xenophobic sentiment, as Szaroszyk is ever ready to sing the praises of Norman Foster's Metropolitan building on Plac Pilsudskiego, for instance, as being "good for the city".

A new vision

Whilst little can be done to reverse the multi-storey skyline the mid-nineties left Warsaw with, the new mayor is on record, (in an interview with the Warsaw Voice, December 20th last year) as promising that the city will from now on be protected from unfettered development. In relation to his re-instituting the post of Chief City Architect, he stated:

"We want to keep Warsaw's development well under control and eliminate chaos. We'll make sure that permits are granted only to projects that are harmonious with their surroundings in terms of size and height and are consistent with local zoning plans. In locations where zoning plans permit only a six-storey building, a skyscraper will never be erected - unlike previously."

What is striking when one talks to members of the council is the degree of unanimity with which they express their views. Despite the fact that it numbers fifteen highly critical and engaged people, they patently share a common vision.

"On the most important matters, we share the same opinions," says the council's Chairman Andrzej Kiciński, "but the details are discussed vigorously, which is why we take votes, though these are only to record strength of feeling one way or the other."

After giving the bad example, as he sees it, of Milenium Plaza near Plac Zawiszy, where he argues that "normally no architect would say this is a place for such a skyscraper", Paweł Detko goes on to claim that in contrast to the spirit of that project, the council's members, "share the common sentiment of European city planning, with buildings on a human scale of six, seven or eight storeys. What we have inherited in the last ten years is an American rather than European tradition." He then stresses, after acknowledging the value as well as power of money, that "it is important that the quality of space also creates some additional value than can be measured in dollars and this factor has been neglected in recent years."

What emerges from these conversations is a determination on the part of the council to advocate a very strict planning strategy for Poland's capital, where no proposed project goes unheeded by its collective scrutiny. Asked to summarise the council's synergised philosophy, Andrzej Kicinski replies:

"That the city has to be covered with plans and that these plans have to be very strict, especially in the most important parts, such as Aleje Jerozolimskie and Plac Pilsudskiego. It is not necessary to have a city full of skyscrapers and it has to be very carefully checked what impact they will have on the cityscape." That the council will strive to protect Warsaw's parks and 'greenness' and encourage the use of public, rather than private transport, are other goals Kicinski stresses it is keen to achieve.