No more Mordors

Feature

Large areas of Polish cities still resemble a kind of urbanised Frankenstein’s monster – built out of random elements from different eras, which instead of delighting those who pass through them, both horrify and dismay them in equal measure. One example, Warsaw’s Służewiec district, has colloquially come to be known as ‘Mordor’ – and has almost become a byword for failed approaches to city planning in the popular culture. This office basin had almost begun to sink under the weight of its own oppressiveness. However, the area is being resuscitated: new residential estates and hotels are being developed, while the city is improving the local infrastructure – and it could even become a surprisingly pleasant place in a few years. Meanwhile, fears that the mistakes of history are about to repeat themselves have been growing over another part of the capital, which is undergoing intensive reurbanisation – the portion of Wola district closest to the city centre. In terms of its functionality the area is being developed in a much more varied way – office towers and hotels are being built, but also many residential estates and retail buildings. And it has much better transport links than Służewiec. This has not, however, put to bed all the concerns that a new Mordor is being built.

The wind changes

Służewiec turned out to be the perfect example of how not to plan a district. And even though you can find similar examples elsewhere in Poland, something has started to change in people’s thinking about how cities should be built. Even developers themselves are now talking along these lines. “Many zoning plans now stipulate that there should be several functions in a given area in order to avoid the emergence of a monoculture. Cities are increasingly moving in this direction and so more varied development should be expected when it comes to larger projects. This makes sense in the context of sustainable urban development,” points out Roger Andersson, the managing director of Vastint Poland.

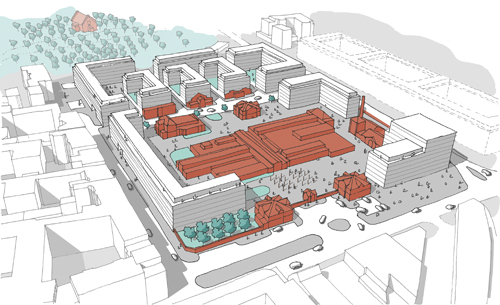

From the developers’ point of view, such a composition of urban development does not need to be a problem and could even open up new opportunities. “This approach is also an advantage for us as a developer – we can build more at the same time. If we were developing just office buildings, we could only do one or two buildings at a time because of the absorption of the market. A large project, therefore, would take us five or six years. In the case of a mixed-use project, we can build more buildings at the same time because they reach different market segments and meet the needs of different types of clients. This also translates into a reduction in costs. In other words: more business, better business and faster business,” argues Roger Andersson. The company has recently invested in more than 5 ha of the former City Slaughterhouse in Poznań. “We plan to build a mixed-use complex there with a large residential section of app. 28,000 sqm and an office complex of app. 27,000 sqm, while another 10,000 sqm will be designated for retail. So far we don’t know what the existing historic buildings will be redeveloped into. This could be a combination of food & drink, retail and office usages. Perhaps cultural space would work best... We need to decide what suits the overall project best. An architect also needs to be selected to design the whole complex,” reveals Roger Andersson. The city council seems to be satisfied with their commitment to a site that has lain derelict for many years. “Projects of such a scale do not just spring out of nowhere. The impulse for them is given by municipal investment. This creates the conditions that enable such projects as the re-development of the site of the former slaughterhouse to get off the ground,” commented Poznań mayor Jacek Jaśkowiak after the purchase of the plot by the developer. “Our activities, as the city council, are focused on returning people to the city centre. We also know what investors need in order to take decisions about projects. And thanks to such decisions, rundown quarters of the city can be brought back to life. This project will restore the splendour of the historic buildings, transforming the area into an architecturally pleasing city centre quarter, filling it with people,” argued the mayor. The administration he heads is hoping to mix up the functions in the city centre so that, for example, residential development can be supplemented by others.

In Warsaw, meanwhile, Vastint is working on a huge project neighbouring the city’s main airport. “We have bought more than 14 ha near the airport from the Military Property Agency [AMW] and are now planning a large mixed-use project of around 200,000 sqm on the site. Our plan is for about half or 60 pct of this to be residential development with around 1,200 units, while the remaining section will contain commercial space, such as 90,000–100,000 sqm of offices, and maybe a hotel or a car park – we haven’t decided yet. The project is at the design phase, so it can still undergo significant changes. Architects from the JSK studio are working on it and we will soon be applying for the site development conditions. There is the chance that we will be able obtain the building permit for the first stage by the end of next year and that we will be able start it in 2020. We want to develop residential and commercial buildings in the first stage – as these functions do not compete with each other. The development of the entire project should take 10–15 years,” explains Roger Andersson.

Vantage Development and Rank Progress will be developing a similar mix of functions in their Port Popowice project in Wrocław. A total of app. 2,000 apartments as well as office and service space are to be built on the 14 ha plot on ul. Wejherowska. The heart of the project will be a revitalised port basin, surrounded by service, restaurants and cafés. “Port Popowice will be a showcase of the western part of the city,” declared the developer.

The more, the merrier

Projects by private investors are just one side of the coin. Without the involvement of cities in the improvement of the transport infrastructure, they would only be made up of isolated islands of new buildings. Thus cities are investing in tunnels, ring roads, viaducts, trams, metro systems, boulevards and other elements of city infrastructure. Some of the largest projects aimed at improving the quality of life in Polish cities are taking place in Warsaw and Łódź. The Capital Integrated Revitalisation Programme is an initiative under which Warsaw city council will spend more than PLN 1.4 bln on projects in the Praga-Północ, Praga-Południe and Targówek districts by 2022. These funds are to be used for investment in new buildings, on renovations of old tenement buildings, as well as for the development of tourism, culture, sport and the local economy together with support for residents. Łódź, meanwhile, has already started to spend what will amount to almost PLN 1 bln on the revitalisation of the city centre. This involves the renovation and modernisation of more than twenty streets and almost 100 buildings, including important monuments.

Major projects require a great deal of work and resources, but above all a clear and coherent plan appropriate for the needs of that city. “You have to realise a vision that is transparent and simple, which everyone will be able to identify with and that no one will be able to challenge in the future. The vision must have a solid foundation if it is going to be able to attract all the stakeholders needed for the project, as was the case with the construction of the Bilbao subway,” explained Daniel Ringelstein, the Europe director of architectural studio Skidmore, Owings & Merrill LPP, speaking in Warsaw at the Places + Spaces meeting held earlier this year by the Urban Land Institute. “Then it becomes easier to finish the original version of the project, even if new projects are being mooted all the time. When the entire community supports the project, it’s easier to stick to the original idea. Basically you need a clear vision, a well-prepared process, an open dialogue, cooperation and the involvement of as many people as possible from the outset. It’s also necessary to properly designate and separate all the different tasks, as well as find the right management team for the project and choose the actual leader of the group. However, the opinions of people outside the team should still be taken into account and you should try to make them all contribute to the project. You simply have to move forward while working with a variety of local groups,” he argued.

PICTURES:Damian Woźniak, board member

of Ghelamco Poland (below):

“One of the strategic goals of our

company is the transformation

of former industrial sites and the

creation of friendly public spaces.”

Port Popowice

project in Wrocław

(above)

The first preliminary

sketches for the

redevelopment

of the City

Slaughterhouse

in Poznań (right)

So let’s talk about the city

The transformation of former industrial zones into attractive modern districts is of particular importance in terms of the cohesion of a city. However, coming up with the right development model is not easy and sometimes it is worth asking all the parties involved. Warsaw city council has started a pilot programme entitled ‘Estates of Warsaw’ [Osiedla Warszawy], aimed at developing ideas for new multi-functional residential estates. “The ‘Estates of Warsaw’ project has been devised to create a model for cooperation between residents and investors, through which concepts for developing selected areas will be drawn up in a transparent, secure, professional and participatory manner,” explains Michał Olszewski, one of the deputy mayors of Warsaw. “Through this initiative we want to build a city that will serve both present and future generations in the best possible way,” he insists. Sites in Żerań in the Tarchomin district were the first to have been considered under the scheme: Port Żerań and Żerań FSO. This amounts to a few hundred hectares of former industrial sites that will now be repurposed for residential and commercial development. Buildings for 4,000–10,000 inhabitants as well as other commercial buildings are to be constructed within the area of the port. Three companies are together planning to develop an exhibition complex with a hotel (Project S8, Arivelia and Global Expo) at the junction of ul. Modlińska and ul. Toruńska. Auchan intends to modernise its hypermarket and neighbouring Leroy Merlin store on ul. Modlińska. Ghelamco, meanwhile, owns 4 ha in the north-eastern part of the Port, where it plans to build a residential estate with 650–700 apartments. The first port pier (app. 8 ha) is being purchased by Okam for the construction of around 700 apartments. The central pier, with port basins on both sides and artificial islands created as habitats for protected birds, belongs to the city. The remaining plots are situated among private land and stretch along the railway line, and thus are less easy to develop. “Our assessment of the ‘Estates of Warsaw’ pilot programme has been very positive. One can only hope that the approaches agreed after much discussion will feature prominently in the study and later in the form of the terms of the local zoning plan,” comments Damian Woźniak, a board member of Ghelamco Poland. “One of the strategic goals of our company is the transformation of former industrial sites and the creation of friendly public spaces. This was the case with Warsaw Spire and Plac Europejski, as it will be with Żerań and the Warsaw Hub project. In the discussions over the development of Port Żerań, interested parties expressed their desire to preserve a large amount of greenery and for public space to be created. I believe that we will be able to meet these requirements. First of all, our plans involve bringing to an end the industrial activity on the site and then transforming it into a residential estate with a public promenade, shops and services on the ground floors and well-tended greenery. We are also open to developing educational buildings within the residential estate,” claims Damian Woźniak. With such initiatives one more thing needs to be borne in mind: “Everything we do when planning cities must make them better for living in and safer. When it comes to revitalisation projects the key elements are always: public-private cooperation, a clearly delineated direction of change, the ability to rise above political divisions and having a long-term vision,” believes Alfonso Martinez Cearra, the general director of the ‘Bilbao Metropoli-30’ association, which for over 25 years has been involved in the revitalisation of the Basque capital.